Ingenious

Richard Munson

W.W. Norton & Co., $29.99

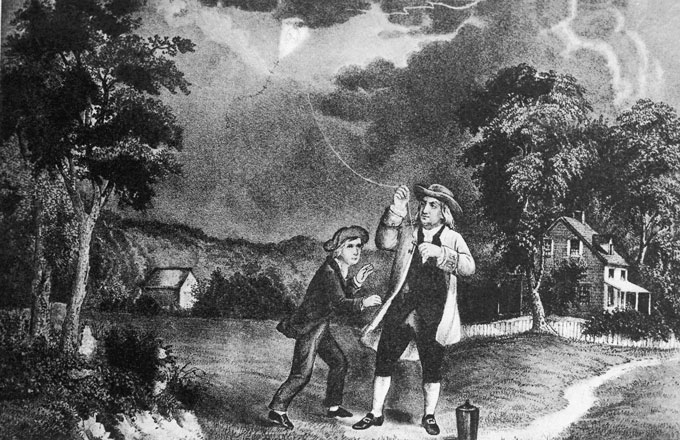

Let’s talk about the kite and the lightning storm. In the public’s mind, Benjamin Franklin’s scientific work has largely been reduced to this one experiment, in which Franklin demonstrated that discharges from thunderstorms are electric in nature (SN: 10/21/11). A new biography of Franklin, titled Ingenious, dispels some of the misunderstandings about that experiment and about Franklin’s science more broadly.

While many accounts of Franklin’s life focus on his role as a founding father of the United States, science was central to his life story, author Richard Munson argues. Far from a mere pastime or quirky hobby, scientific research brought Franklin the fame and clout that enabled his diplomacy. “Science, rather than being a sideline, is the through line that integrates Franklin’s diverse interests,” Munson writes.

The 1752 kite experiment, in which Franklin famously flew a kite during a storm, was more nuanced than sometimes depicted. The kite wasn’t struck by lightning. Rather, sparks emitted from the key attached to the kite’s string revealed the ambient electric charge produced by the storm. And the experiment wasn’t performed on a whim without regard for safety. Franklin was aware of the dangers of electricity and took precautions. “His experiment was neither a lark nor divine revelation,” Munson writes. With it, however, he “converted a mystery into a wonder.”

Franklin’s contributions to the study of electricity went well beyond lightning. He proposed that electricity was a single, fluidlike substance — not two, as others thought. Although Franklin’s theory was an oversimplification, it was a predecessor to the modern understanding of electricity. The fluid could be present in excess or in a deficit, which Franklin described with the terminology of “plus” and “minus,” or “positive” and “negative,” terms that persist today to describe electric charges. Franklin also concluded that the fluid could move or be collected but not created or destroyed, known as the law of conservation of charge. He described the differences between materials that do not transmit electricity and those that do, which he named conductors. Munson notes that J.J. Thomson, discoverer of the electron, said Franklin’s contributions to the science of electricity “can hardly be overestimated.”

The book follows Franklin’s roles in the British colonies in America, the American Revolution and the subsequent nascent period of the new country. As the story unfolds, Munson includes Franklin’s concurrent insights into scientific topics ranging from geology to botany and more. Even at times of intense political negotiation, Franklin’s thoughts were gripped by wonders of the natural world. He was likewise a prolific inventor, and Munson chronicles his work on printing techniques, lightning rods and efficient stoves (SN: 7/17/23).

The biography largely glosses over Franklin’s participation in slavery. Though he eventually became an abolitionist, he was an enslaver for much of his life. Some readers may also wish for more scientific context than the book provides. Franklin’s musings on science are often presented without comparison to current understanding. At times, readers may wonder whether his insights were prescient, or intriguing but wrong.

Instead, Munson focuses on Franklin’s approach to science, which was full of joy. He played scientific tricks. For instance, he fascinated friends by appearing to smooth the surface of a stream simply with a wave of his cane. Franklin had hidden oil within a hollow cane, which he released to coat the water and smooth out its ripples. He slightly electrified the fence of his home. And he prepared a facetious proposal to study causes and remedies for farts. But Franklin also was humble, altering his theories when presented with new evidence and acknowledging failures and learning from them.

Likewise, Franklin’s political views were dynamic — he argued forcefully that the colonies should remain loyal to Britain before embracing the calls for independence. But science, Munson argues, was a cause he fully embraced throughout his life. “He sought out the clever and displayed an almost boundless curiosity, utilizing imagination and investigation to understand the natural and political environments around him.”

If we don’t understand Franklin’s science, Munson says, “we do not appreciate Franklin as well as we believe or as richly as he deserves.”

Buy Ingenious from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.

Source link