The motion of whizzing electrons has been captured like never before.

Researchers have developed a laser-based microscope that snaps images at attosecond — or a billionth of a billionth of a second — speed. Dubbed “attomicroscopy,” the technique can capture the zippy motion of electrons inside a molecule with much greater precision than previously possible, physicist Mohammed Hassan and colleagues report August 21 in Science Advances.

“I always try to see the things nobody’s seen before,” says Hassan, of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

The attomicroscope is a modified transmission electron microscope, which uses a beam of electrons to image things as small as a few nanometers across (SN: 7/16/08). Like light, electrons can be thought of as waves. These wavelengths, though, are much smaller than those of light. That means an electron beam has a higher resolution than a conventional laser and can detect smaller things, like atoms or clouds of other electrons.

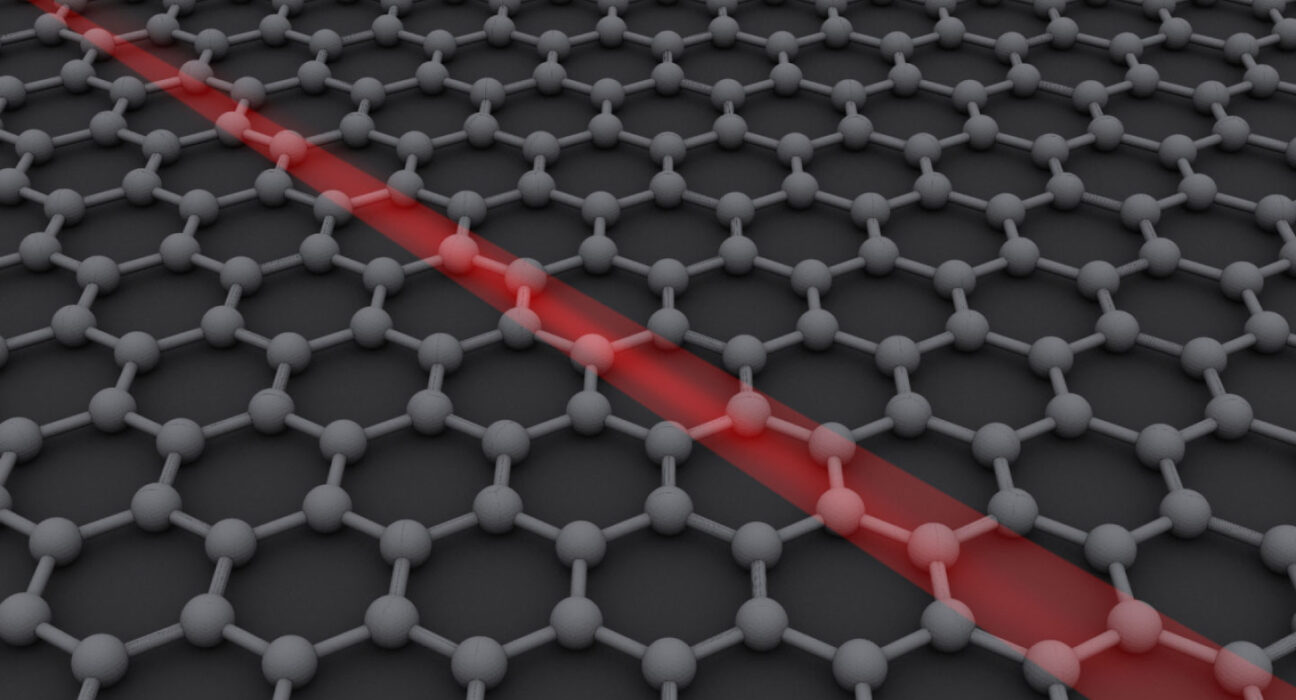

To get their superfast images, Hassan and colleagues used a laser to chop the electron beam into ultrashort pulses. Like the shutter on a camera, those pulses allowed them to capture a new image of the electrons in a sheet of graphene every 625 attoseconds — roughly a thousand times as fast as existing techniques.

The microscope can’t capture images of a single electron yet — that would require extremely high spatial resolution. But by stringing the collected images together, scientists created a kind of stop-motion movie that shows how a collection of electrons move through a molecule.

The technique could let researchers watch how a chemical reaction occurs or probe how electrons move through DNA, Hassan says. That information could help scientists craft new materials or personalized medicines.

“With this new tool, we’re trying to build a bridge between what scientists can find in the lab and real-life applications that could have an impact on our daily lives,” he says.

Source link